Brief History

This is by no means a comprehensive history of Islam in Australia but only an overview to give us a sense of the breadth of the impact that Muslims have made on this country.

Whilst we all recognise that Muhammad was the founder of Islam as we know it today and he delivered the Quran, Islam as a practice of true submission to God has been around from the beginning. We believe that a prophet was sent among the Aboriginal people of Australia many many years before any European or Asians came. However, over time that message was diluted and eventually lost. The Aboriginal people are amongst the most ancient people of all.

However it was not until during the 1500’s that Muslims reappeared in the north of Australia and traded with Aborigines.

The Makassans

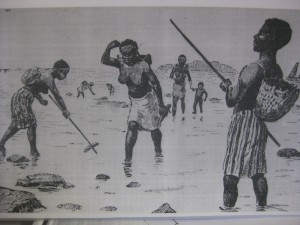

Many centuries before any Europeans had even heard of Australia, Muslims from the island of Sulawesi (today in Indonesia) sailed their small ships called prahus to the northern tip of Australia. These people were Makassan from the islands of Makassar. In the 15th and 16th centuries it is believed that they traded Trepang or sea cucumbers with the Aboriginals in places now called Elcho Island, Gove island and on the mainland near Darwin. The Makassans established a long term relationship with local Aborigines and eventually married with many of the women and some settled in Australia. There is evidence of Makassarese language in Aboriginal dialects and cave paintings depicting the prahus (pictured) and Makkassan huts.

In the 1900’s the newly federated nation of Australia enacted new legislation making it impossible for Makkasans to continue their trade in the north and the Makassan influence was lost with the Anglo-centric dominance of the new government.

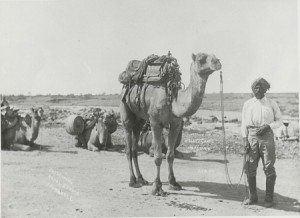

The Afghan Cameleers

In the 1860’s that Muslims were brought to Australia as contracted labourers. There main work involved handling the camels used for outback exploration and for carting and supplying outback settlements with important materials. The contribution of the Afghan cameleers as they came to be called was enormous. However, their life in Australia was by no means an easy one.

“Camel strings was the worst job, as every morning the camels were loaded and in the evening sometimes midnight offloaded. Many a time a windlass was used to draw water, No sooner were we in bed we would have to rise and after the camels we would go, and the same old routine would start over again.”

Jack Bejah 1939 Simpson Expedition

In the 19th century Australia was still a vast and largely unexplored land. Much of the interior was known to be a barren desert, with soaring temperatures and little or no water. Camels seemed a good idea for these conditions, and were imported to Australia. Six camels from the Canary Islands were brought to Australia but only one survived the journey to Australia. In 1846, John Ainsworth Horrocks bought the remaining bull camel and used it for exploration in the Flinders Ranges north of Adelaide.

During the expedition, his camel named Harry, jostled its owner as he loaded a muzzle-loading gun causing Horrocks to lose two fingers and his jaw. The unfortunate died four weeks later and his last request was that they put down Harry the bull.

The next major group of 24 camels came out in 1860, this time for the famous and ill-fated Burke and Wills expedition. They were accompanied by three Muslim sepoys or camel handlers. Not much is known about the fate of these men after the expedition, except for one named Gool Mahomet whose grave is situated by the roadside about 2km out of the outback town of Menindie (where the original expedition set up their base camp).

It wasn’t until 1866 when the first large scale importation of camels began. They arrived on a ship named the Blackwell which disembarked in Port Augusta, loaded with 122 camels and 31 camel handlers, commonly referred to as Afghan cameleers.

This was the beginning of a new adventure, an uncertain future, these men worked for Sir Thomas Elder and engaged in a number of roles, one of them was exploration. The camel was an effective mode of transportation into the dry interior of Australia and several expeditions were made that mapped out places like the Simpson Desert and even involved the discovery of Uluru.

Extract from a journal entry:

“After walking and scrambling two miles barefooted over sharp rocks, succeeded in reaching the summit, and had a view that repaid me for my troubles, Kamran (his camel handler) accompanied me. How I envied Kamran his hard feet; he seemed to enjoy walking about with bare feet while mine were all in blisters.”

William Christie Gosse Sunday July 20th 1875

An estimated 10,000 to 12,000 camels, imported into Australia between 1860 and 1907, were used as draft and riding animals by people pioneering and exploring the dry interior. In 1870 to 1872 camels were the transport used for the establishment of the Overland Telegraph from Adelaide to Darwin. Camels were also used for the supply of goods to Alice Springs, cattle and sheep stations, missions and Aboriginal communities.

With the introduction of the motor vehicle in the 1920’s, the camel was replaced and many were let loose into the Australian Outback. Today, Australia has the largest wild camel population in the world.

These Afghan cameleers contributed greatly to the community of Muslims. They were from diverse backgrounds, tribal regions and age ranges. There was almost not one place in Australia’s vast interior that these men did not traverse and where they went they built mosques.

The first mosque built in Australia was in Marree. It was a simple structure made from mud and logs supporting palms and a thatched roof. Today only a replica of the original mosque stands in the town centre. In Adelaide, the oldest mosque in Australia still in use is in Little Gilbert St, is a wonderful brick structure and the only mosque in Australia with four minarets. It was commissioned in 1885 and completed in 1889.

In Perth, the Afghans raised donations from the Cameleer community across the nation to build their own place of worship, which was finalised in 1905.

Without the use of camels and the assistance of the camel drivers, the Australian outback could not have been developed. The Afghans brought urgently needed supplies to outback communities, they carted materials to build the overland telegraph and were vital during the Gold Rush in West Australia. However, they still encountered discrimination and were marginalised.

In 1901 the new Federal Parliament passed the Immigration Restriction Act which excluded ‘coloured people’ from immigration to Australia. The Act imposed a dictation test, in any language, to be administered to migrants. This was applied to intending immigrants from non-European sources and the language chosen for the test was always one which they did not know.

After this Immigration Restriction Act, resident ‘coloureds’ even had to apply for a special certificate to cross over into another State. This prevented the free movement of the Afghan Muslims and their camels around the interior of the country.

Well known Afghan Khan Zada had applied no less than five times for naturalisation and was rejected every instance.

In 1902 under amendments to the Roads Act cameleers were forced to obtain a special licence to operate in the camel carrying business and had to pay a registration fee for each camel.

In 1903 the editor of the “Barrier Truth” newspaper in Broken Hill, a Mr R.S. Ross, wrote of the ‘Afghan menace’, claiming that the Afghans were a threat to the morals of the community, that their camels were a danger to horses and that they were living in conditions even worse than those of the Chinese.

He told his readers that these Muslims were fierce savages, that they held gross superstitions and that they were thieves. He advanced what was a quite widely held view in the English speaking world at that time, that the Afghans and the other non-white races could not blend with the whites and that they could not marry with whites because ‘the coloured mongrel is a weakling who tends always to sterility and extinction’.

Along with the prevalent racism in society, government pressure and local newspapers demonised the Afghans. Among the most vehement enemies of the Afghans was newspaper editor of the Coolgardie Miner, Frederick C. B. Vosper who received support from 2000 miners to establish the Anti-Afghan League in 1894.

In 1898 the WA colony conducted a Royal Commission into Mining. One of the central issues was the question of Afghans on the goldfields. Gilbert Probyn-Smith who was a journalist asked to give evidence to the Commission. He told the WA Parliament that the Afghans were dangerous.

In the meantime, many Afghans were further marginalised and struggling to keep their industry alive. Thousands of camels were released into the wild as the Afghans could not afford to pay the government tariffs. Many Afghans who could afford to returned to India. But for those who had little money, they were destined to die in Australia. Some sought marital partners in the Outback but this was difficult. Invariably many of the early Afghans married aboriginal women and divorcees or widows from the white community.

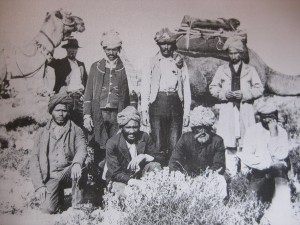

The Life of a Cameleer

From the 1870’s to the 1930’s, Afghan cameleers exercised an important influence in the arid outback. They engaged in exploration, rescue parties and police tracking, laying railway and telegraph lines, setting up water pumps and bores, carrying supplies to, and wool from, pastoral stations, erecting fences, carrying mail and supplying new mining areas.

Most Afghan cameleers came out on one to three year contracts. After their discharge, a small number settled in inland Australia and set up their own camel-breeding and carrying establishments. However, the majority returned to their homelands and to their families in the North-West Frontier borderland of British India, Afghanistan and Central Asia.

In 1901, there were some 600 persons of Indian and ‘Afghan’ origin in the “camel areas” of inland Australia.

When the camel trade died away after the 1920’s, the ‘Afghan’ population rapidly decreased. Many people left Australia, going back to their homelands. Some however, went into other areas of work and chose to stay. Today, many of the old cameleers’ descendants live in Central Australia, in Alice Springs, Port Augusta in South Australia and in West Australia and many more live throughout Australia, though still often in the towns most associated with them.

Post war Migration

The first major migration of Muslims to Australia began in the mid 1950’s with the Snowy Mountains Scheme which brought labour from Southern Europe including at the time Yugoslavia. This meant Muslims from Bosnia, Kosovar and Albania came to work on the scheme and many eventually settled in Melbourne, Adelaide and Sydney. There was no formal organisational structure at this juncture and the first attempts to formalise the loose network of Muslims began in 1964.

Structures in place for Muslim communities

The Islamic community in Australia was, in 1964 only a very small community of Turkish-Cypriots, Arab, Bosnian and Albanian, Fijian Indian, Indian and Pakistani as well as some smaller ethnic groups. The community was not yet large enough to form any associations by ethnicity. There were, however, enough people concerned about preserving their faith to begin a loose federation of the various communities across the country. The Australian Federation of Islamic Societies (AFIS) was formed and this small organisation administered the affairs of the community, especially in terms of raising money to build mosques and schools.

In 1968 the Australian government signed a treaty with Turkey to strengthen the labour force with unskilled migrants through the assisted passage program. This program brought thousands of Turkish migrants who settled in Melbourne and Sydney. By the early 70’s the community was in need of its own places of worship and their first mosque was acquired in 1975. This was an old church in Erskineville (in Sydney) which became the Turkish community’s first mosque.

Also around the same time the Pakistani community with the help of AFIS built the first mosque (in Surry Hills) in Australia since the post war immigration boom.

These mosques catered for the small communities which existed in and around Redfern and South Sydney. The first plane loads of Turkish migrants were housed in hostels around Zetland and the inner city. These communities in the early eighties moved out to western suburban centres such as St Marys, Mt Druitt, East Lakes and Auburn. The Indo-Pakistani community also moved out to Rooty Hill and Blacktown. Today there are two large mosques in Mt Druitt which was built by the Turkish community and in Rooty Hill built by the Indo-Pakistani community.

In 1976 the professional Muslim members of AFIS decided to over-haul the organization and formed the peak body called the Australian Federation of Islamic Councils (AFIC). This was based on a three tier structure of federal council, state councils (9 councils including Christmas Island and Canberra) and local societies. Although the original aims of the body indicated a wide sphere of influence especially in areas of halal certification, mosques, schools, and youth.

NSW

The Islamic Council of NSW (ICNSW) was incorporated in 1976. AFIC was incorporated in 1980 as the peak Islamic body in Australia. ICNSW represented a collective of Islamic societies and organisations in NSW and was a member of AFIC uptil 1999.

In 1996 a dispute had erupted between the ICNSW and the AFIC board. As a result of this dispute the two organizations ended up in court. On 29 August 1999 ICNSW was suspended and a caretaker situation was sought. There was no resolution and subsequently ICNSW was expelled permanently from the federal umbrella organization.

AFIC then created a new state body in 2000 and called it the Supreme Islamic Council of NSW. It did not come into effect until early 2001. The SICNSW had been operating as the state body for almost 2 years until another court dispute arose. In mid 2002 SICNSW sought to remove a society from the council and in August sought to amend its constitution, AFIC said it was unconstitutional and once again the Executive committee suspended the body and during the 2003 Congress elected a new state body calling it the Muslim Council of NSW. The MCNSW is currently AFIC’s representative body in NSW. ICNSW is still operating as an independent body from AFIC and has the support of many societies or associations.

The Lebanese

One of the largest Muslim migrant communities to emerge in Sydney was the Lebanese community. Most Lebanese Muslims arrived after the 1975 civil war and there were thousands who arrived in mainly Sydney (and also Melbourne) and they settled in Canterbury-Bankstown and built their first mosque in Lakemba in 1976. The Lebanese Muslim Association (LMA) manages the affairs of the mosque ranging in services from funeral and burial services to Arabic and Quran lessons. These were the primary services provided by other associations and mosques. They were largely unskilled first generation Muslims who could not speak English with any fluency.

Turks

Also there are now 5 Turkish mosques in Sydney and one in Wollongong . The largest mosque is situated in Auburn and has a lot of influence over the other mosques. It is also a significant player in the Halal Certification Trade.

The Turks do not recognise any title of Mufti (accept those from the Department of Religious Affairs in Turkey – Diyanet) and tend to take their own lead in Islamic affairs such as announcing festival dates. The Turkish mosques in NSW and in Perth are owned as a public trustee by the Diyanet and administered by the local Turkish community. The key role of the Diyanet is to appoint a professionally qualified imam for a term of four years to a mosque. The Diyanet also assists with special events and holy events and provides guidelines for their imams. This is generally government monitored and restricted to religious issues. The imams usually cannot speak English fluently.

There are a number of smaller mosques scattered around south western Sydney. There are two Bosnian mosques (Penshurst & Smithfield) and there are a number of smaller mosques like the South African (Minto), Bangladeshi (Sefton), Indonesian (Dee Why) and Malaysian mosques (Tempe) and larger newly built mosques in Auburn, Guildford, Blacktown and Liverpool.

VIC

Likewise in Melbourne, the first emerging communities were led by Cypriots, Lebanese, Egyptians and Turks. The Albanians and Bosnians were also very active in forming associations. It was not until the early 80’s that schools were established and a number of Mosques were built. The oldest mosque in Melbourne is situated in Carlton and was built by the Albanian community.

Sheikh Fehmi Naji El-Imam was one of the pioneers in Melbourne (migrated in the 50’s) and was based at Preston Mosque. The Islamic Council of Victoria is also a strong institution that provides a number of services to the Islamic community. In the past decade a number of women’s organizations have emerged providing urgently needed services for women. We have also witnessed a new wave of migrants originating from Somalia, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Iraq and Afghanistan in the past decade. The needs of these emerging communities has been focused on settlement, welfare, employment and English training.

Islamic community relations in Melbourne have been slightly smoother and to this day there is only one Islamic council. There are also a number of Islamic schools which all have produced high achievers with excellent academic results. The Turkish community has produced two schools in Melbourne (with several campuses) and currently both Australian International Academy and Minaret College have developed into large and prestigious institutions.

WA

The community in Perth is ironically much older than Sydney or Melbourne, although far smaller in number. The early Afghan and Indian hawkers and cameleers settled in Perth and in 1905 built the Perth Mosque. This mosque is still used by the new generation of Muslims in Perth.

Broadly speaking, the community is dominated by South Africans, Somalis, Turks, Lebanese and Malays/Indonesians. There are four main mosques with a number of smaller centres. The main mosques are situated in Mirabooka, Perth, Thornlie and Marylands.

The University of WA and Curtin Universities have a number of Muslim scholars who are also active within the community. The Islamic Council of WA acts as the peak body for Muslims in Perth but does not enjoy enough support from the main part of the community. The large success story for Perth is the Australian Islamic College which has over 2000 students and three campuses. There are three more Islamic schools in Perth. Like most states there is a Muslim Women’s Association.

Muslims in Perth are quite integrated into the mainstream society and West Australians seem to have readily accepted Muslims new and old alike. This could be attributed to the long history of relations which started with the early Afghan and Indian migrants in the 1800s.

QLD

Brisbane is another unique situation where Muslims have integrated well into the broader community. There are less than 40000 Muslims in the whole state and much of the activity is run by the Islamic Council of Qld. However, there is a strong presence of individual Muslims who work on a variety of matters ranging from welfare, halal certification, women’s issues and academia. Most have some affiliation with the Council.

The Kuraby mosque which was burnt down in 2001 after the September 11 attacks in the US, has now been rebuilt and is a focal point for the community’s activities. The oldest mosque is in Holland Park and was built by the Indian/Afghan community in 1907. There is a new mosque in Durra. There are two Islamic schools in Brisbane; Karawatha and in Gooloongabba.

There are a number of Muslims living on the Gold Coast, Sunshine Coast, Mackay and Rockhampton.

SA

In Adelaide for many years there has been no central body and therefore the community has been generally disparate. The oldest mosque in Australia is situated in Little Gilbert Street and was built in 1886. There are a number of smaller organizations which conducted educational facilities and welfare groups. The main women’s organization is the Muslim Women’s Association of SA.

There are as in other states large populations of Lebanese, Turks (in Murray Bridge), Afghans, and the largest community of Uygur people (from Western China) in Australia. The community is very small and still developing its institutions. The Islamic College of SA is the largest school in Adelaide and also there is an Islamic centre in Park Holme and a small community school. Many Muslims live in the north west suburbs around Gilles Plains where a newly refurbished mosque and school is situated.

Tasmania

The Islamic Society of Hobart is very small. It is one of the members of the AFIC system and holds the same voting power as Sydney and Melbourne. The community is so small, there are very few incidents to report. However, sadly, in 2003, the Islamic Sufi library was deliberately burned down and many valuable books destroyed. The new Hobart mosque was officially opened in 2005.

Canberra

A vibrant and professional group of Muslims reside in Canberra. The Islamic Society of Canberra is an important member of AFIC. Outside of this system is the Canberra Islamic Centre which has built its own centre fully equipped with sports hall/ prayer centre, the largest Islamic library in Australia, a radio studio, an art gallery and functions centre. The group are actively involved with interfaith, media and political lobbying. There is also a new mosque in North Canberra.

Darwin

The Islamic Society of NT is a very small group of Muslims numbering under 1000. They are actively involved in interfaith and media. The community is mainly a mixture of Indo-Pakistani, Indonesian, African and some Chinese Muslims.